The KitchenAid Stand Mixer: A Primer

Originally posted on August 6, 2013 at Obscure Ingredients. This was the first in an occasional series about the history and lore of kitchen gadgets and machines.

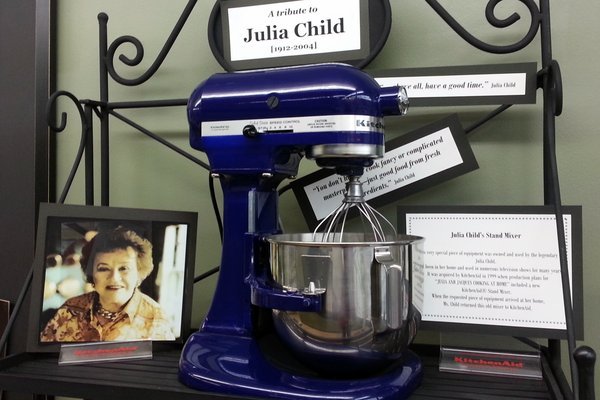

Back in my single days, I used to (sort of) joke that the only way I'd ever be able to afford a KitchenAid stand mixer would be to get married. Turns out I did something far riskier than getting married to acquire my cobalt blue K5 Heavy Duty model—I opened a restaurant, which is another story, or about a thousand of them, for other days and other posts. Said mixer is now 21 years old. Though it has essentially been on light duty since the restaurant years, it still sees a reasonable amount of use, and despite it all, it's still a maintenance-free workhorse in our kitchen. It lives on a sturdy shelf in our kitchen, and gets hoisted down for crepes, pancakes, icing, bread and loads of other chores which I suppose we could do with some other tool, but it sure does every one of them one hell of a lot better than anything else could.

This now-iconic kitchen stalwart can thank a sweaty baker in a hot kitchen for its existence. Herbert Johnson, an engineer at Hobart, the company that still makes the enormous floor mixers you see in bakeries and school cafeterias, correctly decided that some innovation was needed after watching a baker sweat into his dough while kneading by hand. I'm guessing this isn't a particularly unusual event, even now, but I'm on board with minimizing the amount of human-sourced salt added to dough.

The first few years of production were during WWI, when metal shortages prevented the majority of non-military industrial output. Thankfully, the Navy was sufficiently impressed by Hobart's huge, 80-quart mixers to make them standard equipment on all of their battleships, thus ensuring their production through the war.

When business returned to a post-war normal, Hobart got busy on a home model. Early versions were bulky and expensive, but were already impressing home cooks lucky enough to test them. Legend has it that one of the early product testers, the wife of a factory executive, is responsible for the name; she was so blown away by its performance that she exclaimed, "I don't care what you call it, but I know it's the best kitchen aid I've ever had!"

Owning a KitchenAid stand mixer in those days took both healthy biceps and a nicely-padded wallet. They weighed 65 pounds and cost a fortune—$2557.75 in current US dollars—and yet were somehow peddled door-to-door by an all-female sales staff, who were evidently badass enough with their demonstration skills to keep these hulks in production. I searched in vain for images of women in heels and skirts hauling 65 pound mixers door to door, so alas, you'll have to rely on your imagination. Further refinements led to a machine that, by the mid 1920s, was much smaller and lighter, and much easier on the wallet, coming in at about $400 in today's dollars.

The real game-changer was Egmont Arens, whose complete redesign in the mid 30's set the appearance and functionality standards for this now-iconic brand. His award-winning design is both elegant and exceptionally evocative of the time. As you'd guess, it's a hit with collectors.

Arens was not only an exceptionally talented industrial designer, he once owned the famous Washington Square Bookshop in Greenwich Village, where he published nine issues of Playboy: A Portfolio of Art and Satire. It's not the Playboy you're imagining:

Limited to only nine issues over the course of about four years, Playboy was a socially progressive and nearly radical publication in its day, known for including jabbing parody of the rich during the “roaring” 1920s. Associated with the magazine were artists of stature in their day and of renown today, including Georgia O’keefe [sic], photographer Alfred Stieglitz, John Marin, Rockwell Kent, Hunt Diedrich [sic] and William Gropper. Among this group more than one was identified with sensitive political and social views of the day, and even homosexuality. (source)

He went on to be the art editor at Vanity Fair and the editor of Creative Arts. He also operated Flying Stag Press from 1918 until 1927, and published a guidebook, The Little Book of Greenwich Village, which, from what I can gather, was based on the proliferation of "little magazines" of Greenwich Village, the zines of their time. These publications featured the first published works of many in the modernist literary movement, including James Joyce and Marianne Moore. Here's a quote that sums up the little magazine scene well:

A bemused reporter visiting the Village from Oregon in 1922 described the Village's little magazines to his hometown audience as follows. "Every villager will tell you that the soul of this unique colony is best expressed by the bizarre, tantalizing freaks in paper and printer's ink in which free verse, cubistic paintings and ultra-violet sex fiction gives expression to what the villagers like to believe is their tortured, psychic and mystical selves." (source)

I don't know about you, but a tie-in between bohemianism, modernism, literature, art, design and cooking is right in my wheelhouse. And until just now, I'll bet you couldn't have drawn a straight line between James Joyce and a stand mixer.

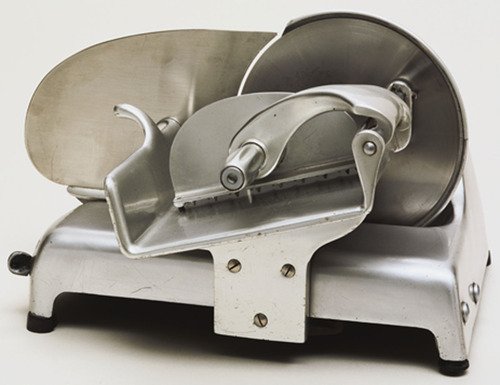

Arens's other designs include watches, elegant lacquered chairs, aircraft, lawn furniture, lamps, and a particularly gorgeous Hobart meat slicer. Sadly, he was also an early advocate of "planned obsolescence", a concept so drearily familiar and so widely adopted by manufacturers of consumer goods that it's difficult to imagine its absence. Ironically, perhaps his best-known contribution to design is also his most durable. His familiar, bullet-shaped KitchenAid stand mixer was introduced in 1937, and has endured to this day. You can even use attachments on these classic models, should you be lucky enough to find one.

Devotion to this machine is widespread and sometimes pretty intense. A list, for your entertainment and enrichment:

An argument about Hobart-era vs. Whirlpool era KitchenAid mixers can be found here.

Molly Wizenberg, a writer and podcaster I admire in her (probably former by now) kitchen in Seattle - notice the Hobart-era KitchenAid on the lover shelf. (Also notice her gorgeous kitchen.)

Want one tattooed to your flesh? Of course you do.

Go ahead and embellish your KitchenAid mixer if you want to

One of my favorite food bloggers, David Lebovitz, lucked into a VIP visit to the KitchenAid factory in Ohio, where every single KitchenAid stand mixer is still made. You'll have to do a little clicking to see his photos—he's not ok with photo sharing, so click and enjoy.

These sexy mixers have earned their reputation for durability—they're tested to replicate 30 years of household use, they're oiled with three times the necessary lubricant, and their product support is second to none. Though they're still not cheap, especially outside of the US, I'm happy to pay good money for a product that the manufacturer expects to last for at least 30 years. And you know, I'm happy to learn that Julia and I chose the same machine in the same color.

Sources

Leolady's KitchenAid Mixer History - Everything you could possibly want to know about KitchenAid mixers. My favorite tidbit? This (admittedly not as cool as the original) copper bowl for the K5. You're welcome.

All Things Considered, September 7, 2009

The KitchenAid stand mixer Wikipedia page

A Visual History of KitchenAid Stand Mixers, and especially Tyler Lizenby’s photos

Inside the KitchenAid Factory, David Lebovitz

More on Egmont Arens here, here, and, of course, here

More on Playboy: a portfolio of art and satire here, and more on the little magazines of Greenwich Village here

A nice summation of KitchenAid's history here, with cool photos

Photo of The Model "H", the first KitchenAid stand mixer. Image Credit: Touring-Ohio.com

The Model H - the original KitchenAid stand mixer.

Arens’s game-changing design.

Egmont Arens, photographed by Jessie Tarbox Beals.

The Egmont Arens meat slicer.